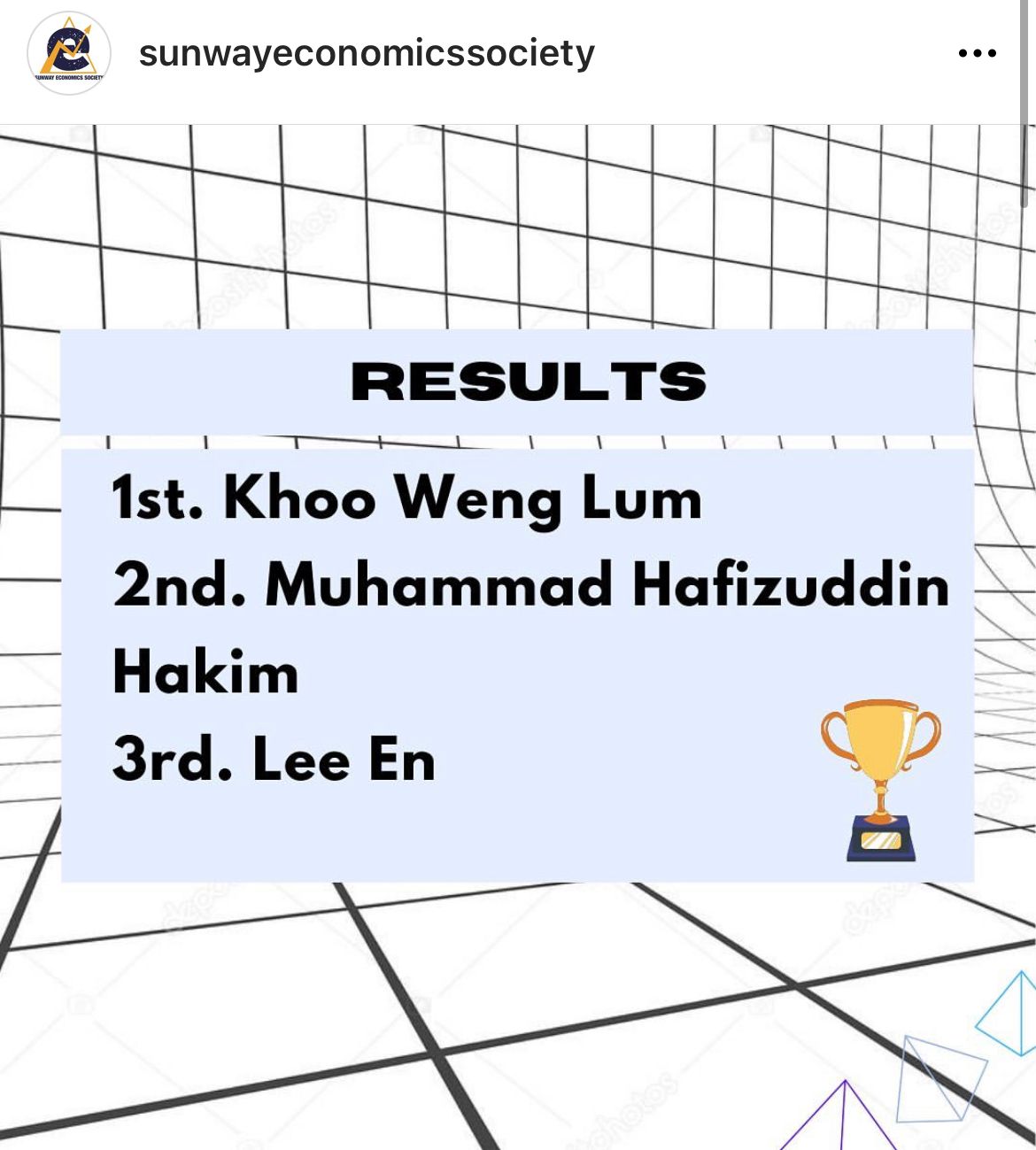

This is my entry for Sunway Economics Society’s essay competition which won me 1st Place.

It is about ways Malaysia can achieve a green economy:

Since COP26 and the 12th Malaysian plan, Malaysia has set out to be carbon neutral by 2050. However, there are no comprehensive details on how Malaysia will get there, with only plans of halting new coal plants, a new energy policy and potential carbon taxes (KPMG, 2021). Getting to net-zero will be a complex issue for Malaysia and it requires drastic measures.

Besides implementing existing technologies such as solar panels and electric vehicles, the world needs new green technologies. According to US climate envoy John Kerry, 50% of the technologies needed for carbon neutrality are yet to be invented (Murray, 2021). Malaysia should play a bigger role in the development of new technologies which can spawn new startups, more high skilled jobs and boost export capabilities. Years ago, M-RNA vaccines were a revolutionary but unproven idea, offering protection against infectious diseases and biological weapons (The Economist, 2021a). In 2013, to develop this risky idea, America’s Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) awarded a small new firm, Moderna, US$25 million. Moderna is now 1 of 2 successful inventors of Covid-19 M-RNA vaccines. DARPA can claim partial credit for inventions of the internet, GPS, drones etc. (The Economist, 2021). The US is now planning other versions of Advanced Research Project Agencies (ARPA) for health and climate change, while copycat versions of DARPA are emerging in Japan, Germany and the UK (The Economist, 2021a).

ARPAs differ from R&D agencies; they by-pass hindrances of bureaucracy, ensuring tangible results. For example, the decision to award US$1 million to invent the internet’s forerunner took just 15 minutes in 1965 (The Economist, 2021a). All of DARPA’s work is contracted out, with directors acting as venture capitalists, aiming to generate specific outcomes instead of private returns. Malaysia should look to build its own ARPA to develop new green technologies like alternative foods, carbon capture, sustainable crops etc. A Malaysian ARPA can follow the model of the Decarbonization Investment Partnership by Temasek and Blackrock (Blackrock, 2021), with funding from the Malaysian government, Khazanah and institutional investors. The new green technologies would help decarbonize Malaysia and the world.

Next, Malaysian businesses need incentives to decarbonize. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a huge part in Malaysia’s emissions, accounting for about 35% of GDP and 18% of exports (World Bank, 2016), but lack incentive to incorporate sustainability. The Malaysian government should set up incentives such as lower income tax rates or subsidies to businesses that meet the government’s emissions target. Trade will provide even better incentive to decarbonize. Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE) should actively promote sustainable exporters. To prevent a Kodak moment, more and more exporters would practice sustainable production and engage with supply chain partners to lower emissions, creating a wider chain reaction. The private sector can step in to provide incentives as well. For example, large conglomerates should take the lead and engage with SME partners up and down their supply chains, supporting their route to sustainability. NGOs must also engage with SMEs, educating them on the importance of sustainability for future operations. For example, the EU has adopted a new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which implements carbon pricing on imports of steel, cement and fertiliser, but could be expanded into other sectors in future phases (European Commission, n.d.). This message must be signalled to all SMEs by the government, private sector giants and NGOs, to prevent Malaysia from losing out on exporting opportunities, especially before other important trade partners start implementing similar carbon pricing mechanisms.

The two strategies above require financing and proper standards. A solution for the former could be issuing green bonds, as 20 other countries have done (The Economist, 2021c). Green bonds can be used to finance infrastructure needed to shift Malaysia towards carbon neutrality or used to preserve the environment, as seen in sovereign bond restructuring by Belize to protect its coral reefs (Stubbington, 2021). We clearly see a strong appetite by institutional investors to incorporate ESG elements into bonds in the restructuring of bonds of Belize, Ecuador and Buenos Aires, Argentina (Stubbington, 2021). Moreover, green bonds have proven to lower borrowing costs, with investors demanding higher yields on comparable conventional bonds. For example, the yield difference for a 10-year German bond is about 0.05 percentage points while Britain’s bonds issued in September had a 0.025 percentage point difference (The Economist, 2021b). The demand for green bonds is clearly present, the German 10-year bond yield gap has risen from 0.02 points a year ago, suggesting that the demand for green debts exceeds their supply; while Britain’s green bonds were oversubscribed 10 times over (The Economist, 2021b).

Proper standards would be needed to prevent greenwashing and ensure full transparency of each firm’s carbon footprint. A board similar to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) should be set up for exporting companies. The board should be independent of government intervention, acting solely with the purpose of conducting proper audits and consultation for carbon emissions and environmental harm prevention. Board members should also have members from international organisations from trading partners to help Malaysian businesses understand the developments of sustainable trade and gain international recognition for its standards. This new audit and standards board could reward Malaysian businesses who comply with their standards, granting access to cheaper financing, exporting opportunities in key markets and greater recognition from environment conscious consumers. According to Deloitte, 28% of consumers have stopped buying certain products due to ethical or environmental concerns (Deloitte, 2021). Malaysia should see this as an opportunity to set itself apart from its competitors in international trade. Any qualifying business who meets the audit standards should receive a certificate of recognition that can prove its environmental credibility to supply chain partners and consumers. The board should not merely pressure Malaysian SMEs but act in goodwill to guide their path towards net-zero.

The above strategies would require governments, businesses, NGOs and consumer cooperation in the short-medium term that would bring long-term benefits towards the environment and the economy.

Appendix

Blackrock (2021). Temasek and BlackRock Launch Decarbonization Investment Partnership. [online] BlackRock. Available at: https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/newsroom/press-releases/article/corporate-one/press-releases/temasek-and-blackrock-launch-decarbonization-investment-partnership.

Deloitte (2021). Shifting sands: Are consumers still embracing sustainability? [online] Deloitte United Kingdom. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/sustainable-consumer.html.

European Commission (n.d.). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. [online] ec.europa.eu. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/green-taxation-0/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en.

KPMG (2021). Net Zero Readiness Index: Malaysia – KPMG Global. [online] KPMG. Available at: https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2021/09/nzri-malaysia.html.

Murray, J. (2021). Half of emissions cuts will come from future tech, says John Kerry. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/may/16/half-of-emissions-cuts-will-come-from-future-tech-says-john-kerry.

Stubbington, T. (2021). Belize leans on coral reefs to drive bargain with bondholders. Financial Times. [online] 17 Sep. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/093f712d-6839-4bb3-a901-9c38f0e0fda8.

The Economist (2021a). A growing number of governments hope to clone America’s DARPA. [online] The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2021/06/03/a-growing-number-of-governments-hope-to-clone-americas-darpa.

The Economist (2021b). A wave of green government bonds is flooding markets. [online] The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/10/09/a-wave-of-green-government-bonds-is-flooding-markets.

The Economist. (2021c). Five financial surprises in 2021. [online] Available at: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2021/12/22/five-financial-surprises-in-2021.

World Bank (2016). “Small is the New Big” – Malaysian SMEs Help Energize, Drive Economy. [online] World Bank. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2016/07/05/small-is-the-new-big—malaysian-smes-help-energize-drive-economy.

- A Green Malaysia

- What is Abenomics ?

- How the rich avoid Paying Taxes

- What is a Free Trade Agreement ?

- How Malaysia’s Lockdown has impacted the Global Economy.

- Biden’s biggest Failure

- What is a Digital Currency ?

- What is Quantitative Easing ?

- How Interest Rates affect my Overseas Studies

- The different Institutions on Wall Street (Part II)

- Seeing the effects of Climate Change

- What is Net-Zero ?

- How the 2007/08 Housing Bubble burst

- Malaysia’s Brain Drain

- The different Institutions on Wall Street (Part I)